We all know the proverb about the inevitability of mortality and taxes, and that certainly applies in the world of investing. Of course, the main reason we invest is to make money, but it’s also important to understand how the government’s share is calculated and how it affects your outcomes. The tax efficiency of your investment activity can have a major impact on how much of your portfolio is actually available for your purposes. In other words, once you’ve got a grasp of the basics of how taxation affects your investments, you’ll be in a position to make better decisions about your investment activity.

Four Kinds of Taxes

The first thing to understand is that four types of taxes can be levied on your investments. Two of them are related to profits you realize when selling assets, and the other two are related to the type of income generated by your assets.

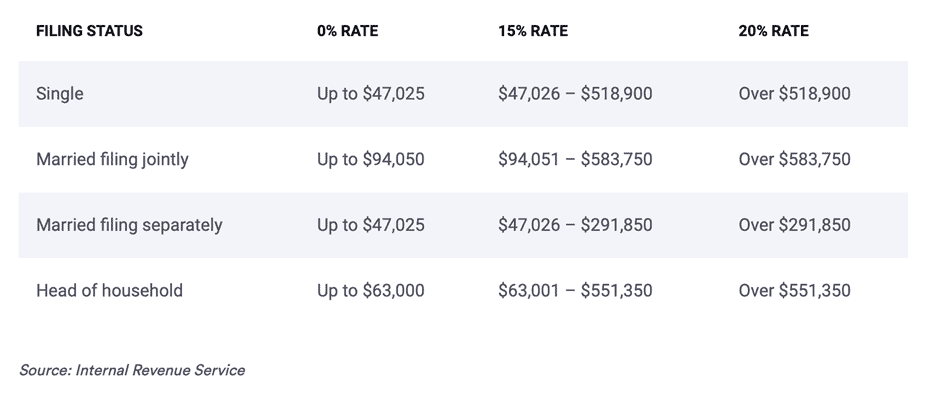

- Long-term capital gains. A long-term capital gain results when you buy an asset, hold it for at least a year and then sell it for more than you paid for it. The percentage of tax paid depends on how much other income you have, but the rate on long-term gains is typically less than that paid on earned income (such as a salary). There are three different rates: 0%, 15%, and 20%. Here’s a chart of the tax rate on long-term capital gains for income reported in 2024:

So, if your income is $47,025 and you have a long-term capital gain, you would pay 0%. As your income rises past certain levels, the percentage goes up to a maximum of 20%. This means that a person can be in the highest marginal tax bracket for ordinary income (37%) and only pay 20% tax on their long-term capital gains.

- Short-term capital gains. You can probably figure out from the name that this tax applies to gains on assets held less than a year. Short-term capital gains are taxed at the same level as your earned income.

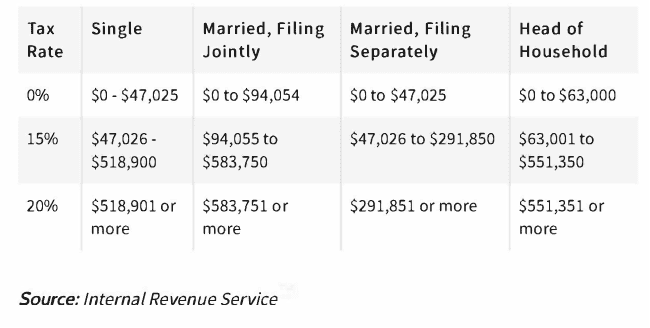

- Dividends. People who own stock (equities) are often entitled to receive a share of the company’s excess earnings in the form of dividends. Similar to capital gains, there are two types of dividends: qualified and ordinary. Qualified dividends are paid from a company’s after-tax earnings, and for that reason the owner of the stock gets a break in the form of a lower tax rate. Like long-term gains, qualified dividend income is taxed at 0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your income level:

Ordinary dividend income, like short-term capital gains, is taxed at the same rate as earned income.

- Interest income. Interest earned on bank accounts, bonds, and other interest-bearing investments is taxed at the same rate as earned income.

Any of the above types of income earned in a regular investment account must be reported on your tax return, and you must pay the requisite amount of tax. The exception, of course, is when you hold your investments in an IRA, 401(k), 403(b), or other tax-advantaged account. Income generated by assets held in these accounts is not taxable, which means that the value of the account can potentially grow much faster, since money that would otherwise go to the IRS remains in the account and continues to grow and compound. Depending on the type of account, you may be required to pay taxes on funds withdrawn from a tax-advantaged account when you reach retirement age, but often, when assets are able to spend years achieving non-taxed growth, the extra earnings can make a real difference in funds available to fund a comfortable retirement.

What about Losses?

On the other hand, the value of assets doesn’t always go up, at least in the short term. Just as there are long-term and short-term capital gains, there can also be long- and short-term capital losses, if you sell an asset for less than you paid for it.

But this can be a silver lining to assets clouded by loss. Sometimes, investors may wish to employ a tactic called tax-loss harvesting, which allows them to offset gains in one part of the portfolio with losses in another—resulting in a lower tax bill.

Here’s a simplified illustration. Suppose you own Mutual Fund A, which you bought for $50,000. You held it for a year, and in that time, it went up by $10,000 and is now worth $60,000. If you sell it, you will have a long-term capital gain of $10,000. But suppose you also own Mutual Fund B, which you bought a year ago for $50,000. Today, it is only worth $40,000. If you also sold Fund B, you would “harvest” a long-term loss of $10,000 that can be used to offset your long-term gain of $10,000 in Fund A, resulting in a net capital gain of $0. You would owe no capital gains tax.

Some investors may want to replace the assets sold at a loss to maintain their desired portfolio asset allocation. In such situations, they need to be sure to observe the IRS’s wash sale rule, which specifies that they must wait at least 30 days before repurchasing an asset that is “substantially the same” as the one sold at a loss. Failure to do so would mean that the loss would be disallowed.

Keep in mind that long-term capital losses must first be used to offset long-term gains; if there are no more long-term gains available, then the loss can be used to offset short-term gains. The same is true for short-term losses: they must first be used to offset short-term gains, and then any remaining losses can be used to offset long-term gains.

As you can tell, using a good strategy around tax-loss harvesting is important. A professional, fiduciary advisor can be extremely helpful in helping you decide where your best tax advantages lie in these situations. In fact, guidance in making the most tax-efficient decisions for your investments is one of the most important services a financial advisor can offer since tax efficiency can significantly enhance the performance of your portfolio over the long haul.

At The Planning Center, our goal is to help our clients design long-term financial strategies that are both tax-efficient and tailored to each client’s specific needs, temperament, and resources. To learn more, visit our website to read our article, “Tax-Loss Harvesting Explained.”